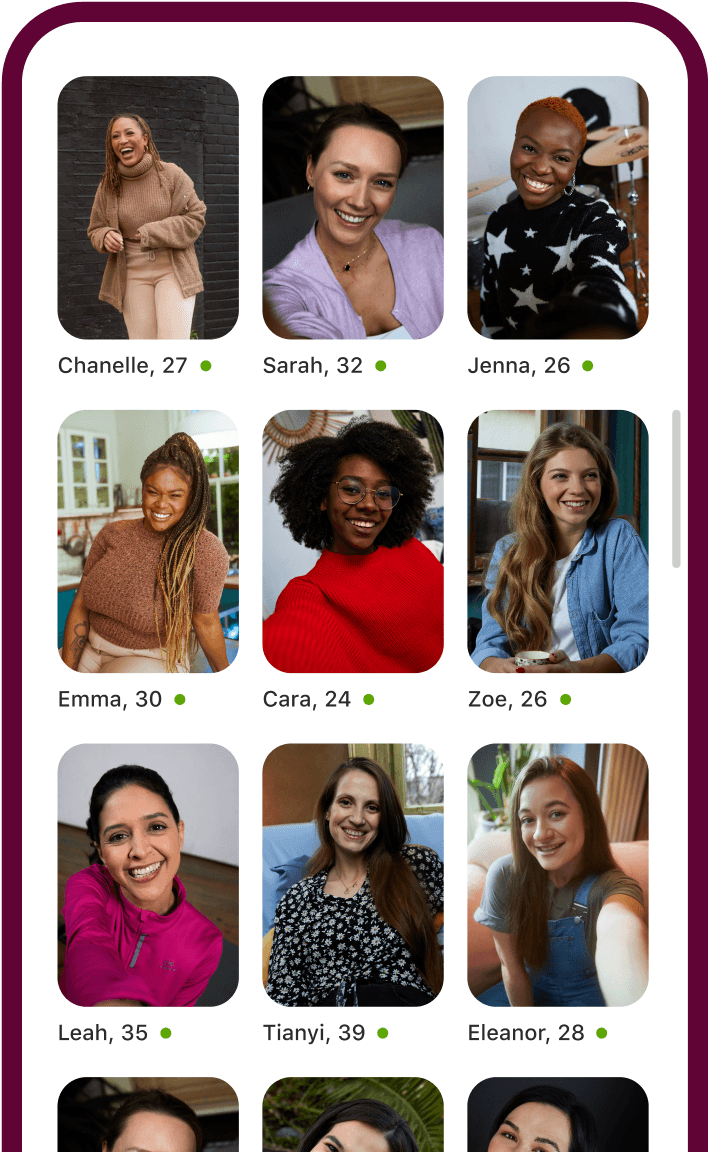

Here’s to dating with confidence.

Helping to put more of the real you in,for dating you feel good about.

We’re all about confidence.

With our latest tech that helps combat fake, scam and spam accounts, you can trust that you’re talking to genuine people.

Our support and safety tools help put the real, most confident you out there — so you can find the relationships that matter.

Our support and safety tools help put the real, most confident you out there — so you can find the relationships that matter.

Ready to chat now?

There’s no need to wait for a match.

Dive into the chats that go a little deeper, and get straight to the good stuff. You know, the bit where you really get to know each other.

Dive into the chats that go a little deeper, and get straight to the good stuff. You know, the bit where you really get to know each other.

Meet people who want the same thing.

Get what you want out of dating.

No need to apologise.Just want to chat? That's OK.

Ready to settle down? Love that.

And if you ever change your mind, you absolutely can.

No need to apologise.Just want to chat? That's OK.

Ready to settle down? Love that.

And if you ever change your mind, you absolutely can.

Safety first,

second, and always.

Your safety is our number one priority.Our Safety Centre is a knowledge hub, containing all the support you need to date with confidence.

We know what we’re doing.

Trust us. We've brought millions (and millions, and millions) of people together since 2006.

100M+ Downloads

Google Play Store

Google Play Store